The American experience in the First World War has shaped the United States politically and culturally until the present day. The American Soldiers of the Great War, or “Doughboys” as they are affectionately known, had an experience while at the Front, that has been passed over in many of today’s history textbooks. With the passing of the last Doughboy, Frank Buckles, in 2011 the final voice of the Americans who experienced the Western Front was lost. Now many students of history prefer the GI of the Second World War, or Billy Yank and Johnny Reb of the Civil War. This leaves much in the way of research to be done on the average Doughboy. As historian Edward G. Lengel puts it; “The Doughboy, meanwhile, remains a mystery.”[1] I became infatuated with the story of the Doughboys after visiting the site of the Western Front for the first time. As far as I knew, my family had not had a very active connection to the military so I was surprised to learn from my grandmother, who was traveling with me, that her uncle served during the Great War. As I began the journey into finding out more about him, I simultaneously found a love for the Doughboys, and their lives on the Western Front. My great-great uncle’s story is typical of those of many American soldiers of World War One. By following his experiences during the First World War, I hope to highlight a typical experience of an average Doughboy and encourage others to follow on the same path.

Morris Polsky was born in Lincoln, Nebraska sometime in the 1880s. His parents were Eastern European Jews who had immigrated only a few years previously. Morris enlisted in the United States Army on May 5th, 1917. By May 7th he was at Fort Logan near Denver, and by the 16th was at Fort Scott in San Francisco. Finally, on the 22nd of June he found himself at Fort Bliss near El Paso, Texas, where he completed his training as an artilleryman. He proved so proficient that by the 17th of September, he was appointed Sergeant. His was assigned then, as an NCO, to the 18th Field Artillery Regiment. He would serve with Battery A as their Supply Sergeant. Morris had no previous military experience. The fact that he was so rapidly promoted shows us that the Army’s command structure was not prepared for the great influx of men into the military after war was declared. As in Morris’ case, it had to be rapidly expanded.

Training within the camps across the United States was rigorous. Yet it was also incomplete due to the many shortages that the Army faced when war was declared. There were almost no artillery pieces for the men to train on, and those that were available dated to the previous century. However, the need for more American troops in theatre prompted unprepared units to be sent to France to complete their training under French instructors, who had learned their skills in actual combat. The 18th Field Artillery, now part of the 3rd Infantry Division, embarked upon transport ships at Hoboken, New Jersey on the 23rd of April, 1918, arriving at St. Nazaire on the 12th of May.[2]

Arriving in France, Morris and his unit immediately were sent to a French Artillery camp which dated back to the Napoleonic Era. It’s clear that he immediately took a liking to the French landscape as he wrote: “Our Camp is called Coëtquidan; it is one of Napoleon’s old artillery camps. Understand the name means ’The Camp of Death‘. It is certainly beautiful around here.”[3] While the name in fact, does not mean camp of death, the rumors Morris was hearing were a premonition of things to come. It was at Coëtquidan, where the 18th received their training and assignment to French 155mm Schneider howitzers, to complement the other artillery regiments of the 3rd Division which had been issued with lighter 75mm guns. All of the artillery pieces issued to the troops were surplus French cannons and howitzers. The United States had failed to appropriately react to its entry into the war by mobilizing its armaments (especially artillery) industry; unlike the country’s reaction in World War Two. In fact, production was so bad for the 155s that the first American built howitzer did not reach France until after the Armistice had been signed.[4] Cooperation with the French was therefore the main strategy to train and equip the American artillery. Much like the artillerymen of the 3rd Division, the artillerymen of the 1st Division also received training from the French, as explained in their post war history:

” The French teachers were confronted by the task of imparting in a few short weeks the technical and tactical knowledge gained by them in three years of war on the western front. While the American artillery had been taught in their own country the correct principles in the use of the arm, the application of the methods developed by the war differed materially from previous conceptions of the employment of artillery.[5]

Morris and the artillerymen of the American Expeditionary Force had to go from their various camps back in the United States, where they were drilled in tactics more adequate to win the Battle of Gettysburg, to taking in as much instruction as they could from the French artillery instructors who had gone through modern battles such as Verdun. It is an understatement to say that when the American gunners arrived in France, they were woefully under-trained as well as under-equipped. However there was little time to perfect the art of modern war.

By July the training had to cease, the Germans were making a push towards Paris. Morris and the 3rd Division were deemed ready for combat operations and sent to Chateau-Thierry along the Marne River. Hotly pursued by the Germans, the French army retreated from the far side of the river. Morris and the 18th Field Artillery were transported from their camp to the front by train. On July 11th, 1918 he had his first experience with the front lines:

“Went through outskirts of Paris this p.m. Saw the Eiffel Tower. Several hospital trains, crowded with French, on siding near us. Makes one feel kind of funny. De-trained at mid-night, in pitch darkness, about 10 miles behind Front. Saw flashes of the guns for the first time, in the north. Makes me feel a little funnier. Did a good job unloading, harnessing and hitching horses, all in the dark and rain. No lights allowed. Left for the line.”[6]

When the Germans reached Chateau-Thierry, they were met by the 3rd Division, who held them off. In honor of their valiant actions there, the 3rd Infantry Division is to this day known as the “Rock of the Marne” division. Even with the victory, things in the 18th were not pleasant. On the 15th of July Morris’ unit suffered its first casualties during a German bombardment.

“German shell hits top of tree, about 30 feet to west of where Dougherty[7] and I are laying. Kills Carlson and Hall out of my section.[8] They are still alive when they are carried to dressing station, but they are in bad shape. Both are filled with shrapnel and are unconscious. Hall thrashed and kicked around for a few seconds then passed out. As this is war. Hall is only a kid, about 17 years old. “Swede” Carlson is about 25. They were Buddies, always together.”[9]

As Morris said, “this is war”. Arnold Hall lied about his age when he enlisted. He was from Pennsylvania and is buried in Aisne-Marne American Cemetery Plot B Row 2 Grave 39.[10]This was only the first battle for Morris, the 18th Field Artillery and the 3rd Division. The 3rd had held firm along the Marne on the 15th of July. Even though Morris witnessed the first deaths in his unit during what is now called Second Battle of the Marne, the Division broke the German attack and in some places created the opportunity to counter attack.

The only German unit to cross to the Allied side of the river, the 6th Grenadiers, was mauled by American rifle and artillery fire and fled back in disorder. Historian Michael Nieberg points to the action on July 15th as one of the major turning points of the war, giving the Allies the power to push the Germans when they were overstretched, exhausted, and coming off of a failed attack against fresh American units.[11] One line from the 3rd Division’s official after action report of the battle gives particular notice to their effectiveness when it states: “On the front of the Third Division there are no Germans south of the Marne, except the dead.”[12] On July 25th, Morris unit was moved into a new firing position on the battlefields of July 15th, he witnessed the carnage there:

“Pretty quiet this a.m. Finished our trenches. Buried more dead Germans scattered over hillside. The odor is terrible. Bodies have been laying out several days and are blackened by sun. Also buried several American Doughboys. Many letters laying around near bodies.”[13]

After the Marne, Morris and the rest of the 3rd Division were pulled off the line and sent into rest billets. Morris and the artillerymen around him finally had some time to relax. They were all deloused and paid. Because of his rank of sergeant, Morris was allowed to roam a little bit. He and his friend Dougherty were billeted in a destroyed farmhouse which they attempted to fix up. In his own words Morris importantly notes that it was the; “First time we’ve slept under a roof in about seven weeks.”[14]

While being billeted in French homes many Doughboys began to get on friendly terms with the locals. In the words of the famous song of the war “How you going to keep them down on the farm, after they’ve seen Paris?” However not every interaction between the American Soldiers and French Civilians was happy. Morris faced one such instance when the owner of the house he was staying in returned home:

“Old woman in whose home we were billeted arrived from the rear. Was heartbroken when she saw the place. Practically all the furniture gone and the house nearly in ruins. Her husband killed and no word from her son. Got some food for her at the battery kitchen, but she wouldn’t eat.”[15]

The sights of war could be found everywhere that Morris and the other Doughboys went in the rear areas. There wasn’t one spot in their area that wasn’t the front line at one point, or at least, in range of the guns.

Shortly after the run in with the woman of the house, Morris traveled into the now cleared town of Chateau Thierry. As a young soldier from Nebraska, the beauty and the destruction intrigued him:

“Went to Chateau Thierry. Tried to find something to eat that we could buy. Purchased can of chocolates from Y.M.C.A. Looked over the town. Went up to the old castle on bluff overlooking city. Built in the year 1200. Crossed Marne River on pontoon bridge. Our artillery had knocked down old bridge to prevent Germans from coming across. River is almost in center of town. Buildings pretty well battered up. Our 7th Machine Gun Battalion held this bridgehead against the Boche on May 31st. First action our Division had seen.”[16]

Rest and training continued for Morris and the rest of the 18th through August, when they were sent back into the fight. This time it would be as part of the Battle of St. Mihiel.

The 18th Field Artillery was temporarily assigned, along with the rest of the artillery of the 3rd Division to the 1st Division for the American attack. Morris’ diary is completely missing the pages covering the days of the battle, but current historians have covered it in depth. Mark Grotelueschen describes the successes seen when the combined artillery of multiple divisions focused their fire to support the attacking infantry of only one. Morris and the thousands of other gunners fired a rolling barrage, a series of bombardments that quickly shifted up to be as close to the front of the advancing American infantry as possible, while not harming them. The Soldiers of the 1st Division under this cover of fire rolled over the German lines, and took all of their first line of objectives in only an hour and a half.[17]

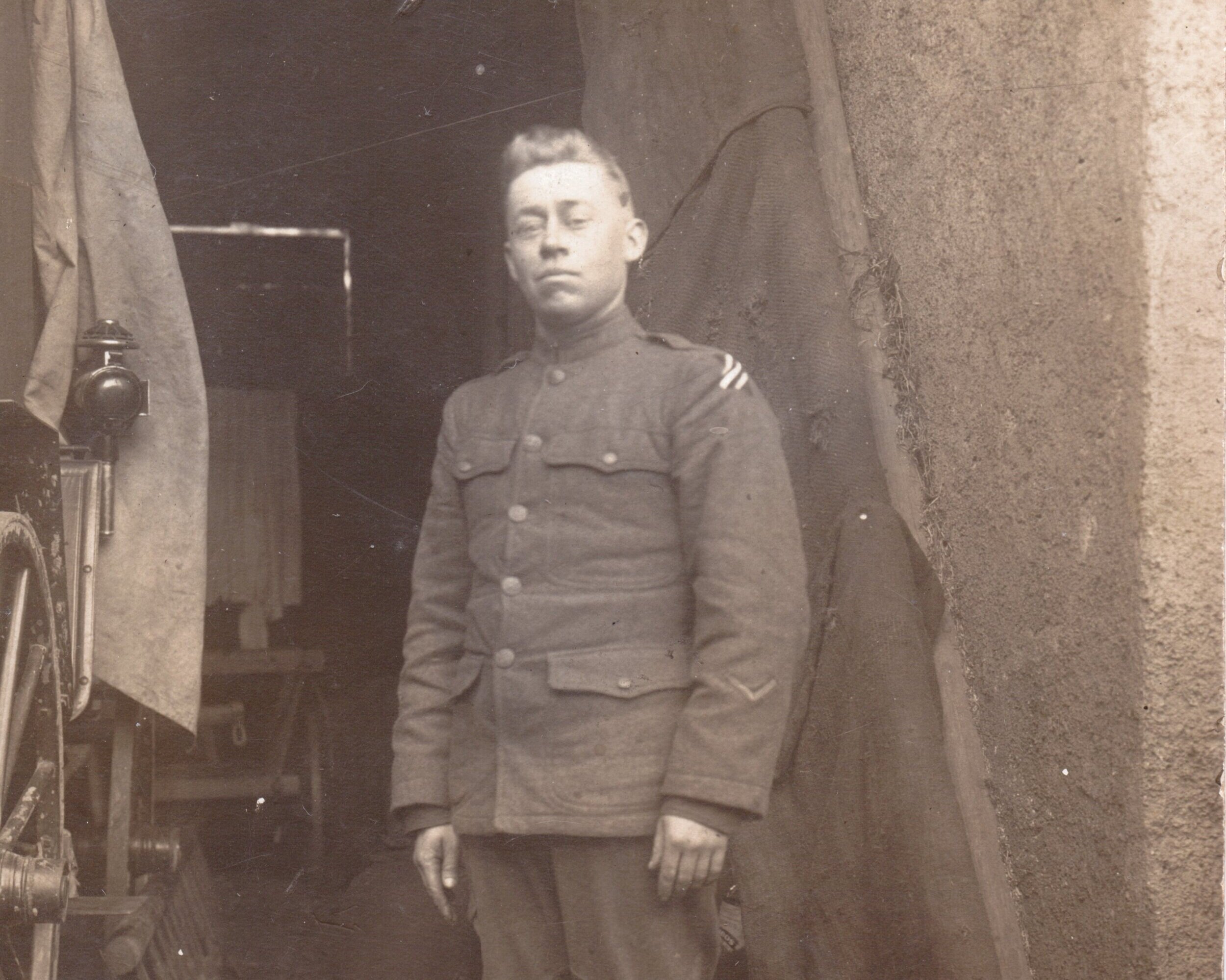

Doughboy in Camp.

Immediately after the success of the Battle of St. Mihiel, preparations were underway for the major American battle of the war, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. At the forefront would be the 3rd Division, covered by their artillery. On September 25th 1918, Morris and the 18th Field Artillery opened fire: “Began terrific barrage fire about 11 p.m. heaviest that I have ever heard. [sic] Continued all night. Understand that this drive is to be on entire front and if successful may mean end of war.”[18] The infantry in front was successful, and the field artillery began to move up to new firing positions. Morris was moving into the Argonne. As Medal of Honor recipient and veteran of the Offensive Alvin C. York would later say; “God would never be cruel enough to create a cyclone as terrible as that Argonne battle. Only man would ever think of doing an awful thing like that.”[19]

Morris and the artillerymen around him had their work cut out for them. By the end of the Offensive (which lasted from September 26th until the Armistice on November 11th) the American artillery fired more shells than the Union Army fired during the entire four years of the American Civil War.[20] Morris saw the combined effects of his gunners as well as the infantry advance on that first day of the big push: “Prisoners coming in by the hundreds. Advanced about 5 miles this afternoon.”[21]

After the first several days, the American attacks started to bog down in the horrible conditions of the Western Front. On September 30th Morris detailed these conditions: “Terrific fire continues. Turned cold today. Slept in a puddle of water last night, wind blew over our pup tent upon us. Let it go. Mud is 12 inches deep around here.”[22] The intensity and confusion of the battle was present at all times even for an artillery unit. On October 2nd a rumor circulated among the batteries that they were to be ordered to the rear. On the 3rd Morris recorded:

“Went forward today instead of to the rear. Hiked all night. Stopped about 3 a.m. Thought we were to stay here as Dougherty, two other fellows, and I beat it off and went to sleep. When we awoke after daylight, the outfit was gone. It was a beautiful day as we started looking for them. Saw several air fights. Watched French anti-aircraft gun in action. Found shoe alongside of road, it was occupied by a foot, cut off at the ankle. German plane brought down near us. Rushed over but soon were ducking for cover as a bunch of Boche planes came over and bombarded hillside where plane had fallen. Finally found outfit late in day, in position at Montfaucon.”[23]

The constant state of danger never stopped. It exhausted every Doughboy both physically and mentally. As one Doughboy, Sergeant Major James Block would say: “The mental strain was maddening, the physical strain exhausted us, yet we had to be alert.”[24]

After encountering the foot in the road on October 3rd the danger did not stop, nor did it on the 4th. October 5th found Morris and the 18th in “an apple orchard about ½ miles from Montfaucon. Germans bombard this place day and night.”[25] Also on the 5th disaster struck the unit as a German shell hit a dugout occupied by the Regimental Gas Officer, Lieutenant Frederick Edwards, and the 18th’s French liaison officer, Lt. Doran. Morris records simply that Edwards was seriously wounded, when in fact, he had been almost cut in two by the German shell. He died early the next day at the American Red Cross Military Hospital #114. He was the only son of a prominent minster in Detroit. One of the nurses on the ward, Marjorie Work later wrote his father; “He is your only son, I know. I know, also, how much you will miss him. But, I did want to write, just to tell you how bravely he died for his country and that his love ones might live in peace, real peace.”[26]

Morris continued with the 18th even after the unit began taking heavy losses. On October 9th the unit almost underwent catastrophe when a:

“Big shell dropped in middle of outfit and killed 19 horses. Not a man was touched. Someone is certainly watching over us, as there are over 200 men in and around the horses. Several more shells dropped real close but no more damage was done as we had all gone into our holes. Seems like they finally have our range. There is horse meat all over this countryside.”[27]

The next day the 18th moved the rest of their horses back an entire mile to save them from future destruction. The Germans became more desperate over the next several days as countless barrages of gas shells landed among Morris and his unit. While the shelling was sometimes off target, it was nonetheless intense. On October 14th, Morris recorded a “heavy barrage last night and this morning. Roberts and Bliss killed by German 77[mm], Roberts instantly, Bliss had half his face and one hand shot off but lived for a short time. Heard that Germany accepted peace terms.”[28] The Armistice was still a month off, yet Morris’ war was about to end.

On October 17th Morris records simply “Got sick today, couldn’t sleep at all.”[29] His situation only continued to deteriorate in what he thought was simply stomach pains. On October 23rd he visited a Doctor at a forward field hospital for the second time, receiving some medication just as the hospital was bombed by the Germans killing several patients.[30] Finally on the 3rd of November, he was taken to Evacuation Hospital #10 with three wounded soldiers. November 5th saw Morris on a hospital train packed with wounded men and no water. Finally on the 6th, he reached Base Hospital #30 in Royat. For the next several days he was left alone in a room, and examined by various doctors. Finally on the 10th he was moved into a large hospital room with numerous other patients. A soldier in the bed next to him asked him what was wrong. He replied saying that his stomach was hurting him. The soldier simply laughed at Morris and asked him “what the hell I was doing in the typhoid ward.”[31] That was the first realization of his true sickness; Morris wrote that he was “Too sick to care much anyway.”[32] Morris had contracted Typhus although, in an interesting example of how families embellish their memories, we were always told that he had been injured in a gas attack. The truth wasn’t recovered until his diary resurfaced a few years ago.

Morris passed in and out of consciousness for the next few weeks. He records no mention of the Armistice or the prospect of going home, only the deaths of the men sick around him. On November 22nd, he managed to eat a full meal for the first time since October 20th. His situation slowly began to improve from there, even though as he estimated, he was down to “90lbs, soaking wet.”[33] He finally managed to sit up in his bed on December 11th, and returned to his unit just after New Year’s, 1919. He would be returned to the United States and mustered out shortly after. The effects of his run in with Typhoid would disable him for the rest of his life. Morris would ever have any children and would not get married.

It would be impossible to say that my great-great Uncle’s experience was typical of the average Doughboy during World War One, for each individual American soldier had a unique experience of their own. However, Morris’ story does highlight many of the points which are brought up in numerous other accounts. Life at the front for the American Soldiers and Marines was a horrible experience. While their time at the front was brief compared to the soldiers of other nations, the casualties suffered by American forces were still incredibly heavy, making World War One our third bloodiest conflict. Morris became one of those casualties in another experience shared with many other participants in the war, disease. While he survived his bout of Typhoid, many others around him did not. Even more succumbed to the Spanish Flu which was then spreading around the world. Morris’ diary recounts the war from his perspective, yet similar experiences were had by millions of other Doughboys. Most of their stories have yet to be shared. It is up to their descendants and future historians to bring to light their wars, and show that the American participation in the Great War is something that needs to be studied until all of the stories are known.

Dedicated to Morris Polsky, the men of the 18th Field Artillery, and all members of the AEF.

[1] Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918 (New York: H. Holt, 2008), 5.

[2] Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988), 47, doi:http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/023/23-2/CMH_Pub_23-2.pdf.

[3] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[4] Robert H. Ferrell, America’s Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918(Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 6.

[5] “Training,” in History of the First Division during the World War, 1917-1919,, comp. Society of the First Division (Philadelphia, PA: John C. Winston, 1922), pg. #25-26.

[6] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[7] Morris’ close friend since artillery training at Fort Bliss.

[9] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[10] “American Battle Monuments Commission,” American Battle Monuments Commission, Burials, accessed April 26, 2015, http://www.abmc.gov/.

[11] Michael S. Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 116.

[12] Ibid.,114

[13] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[17] Mark E. Grotelueschen, The AEF Way of War: The American Army and Combat in World War I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 114-117.

[18] Ibid

[19] Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918 (New York: H. Holt, 2008), intro.

[20] Ibid.,4

[21] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[22] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[23] Ibid

[24] Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918 (New York: H. Holt, 2008), 201.

[25] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[26] Frederick Trevenen. Edwards, Fort Sheridan to Montfaucon; the War Letters of Frederick Trevenen Edwards (Deland, FL, 1954), 282.

[27] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[28] Ibid

[29] Ibid

[30] Polsky, Morris. Diary, 1917-1918. Privately Owned by Author’s Family

[31] Ibid

[32] Ibid

[33] Ibid

Leave a comment